From the birth of CERN in 1954 to the start of digital photo capture, more than half a million of film pictures (B&W and colours) have been shot to illustrate the installation of the experiments, the details of technologies, the life at CERN, the visit of VIPs or also to backup presentations during conferences before the use of presentation software.

Started in 2016, the CERN Digital Memory project has focused on the digitization of all CERN fragile Multimedia assets with the main objective of building an OAIS Archive platform with both analog digitized content and digitally born assets. It also looked at different ways of exploiting the digital archive in innovative ways - so that old deprecated archival material comes to a new life through modern technologies.

While the oldest colorless negatives (120’000) were treated in 2014 mostly to provide an easy access, it was decided to treat the color collection of slides and medium formats (300’000) with preservation criteria in mind, working with expert contractors. The available material centralized at CERN Photo Laboratory was globally in good state, even if some of the slides required careful handling as they could be slightly pasted with the plastic of the envelops. All this data is now been migrated into uncompressed RGB TIFF 16 bits/channel depth files with a resolution of 4800 ppi for a 24x36mm size.

But while building the inventory, it was asked to all the departments to collect existing analog multimedia supports, as it could be that images of interest were shot or circulated on CERN sites without having a central copy in the Media Lab cupboards. Unexpected content were found in various locations. One of these was a complete cabinet of 35 mm color slides spotted in the corner of an underground storage room of one of CERN experimental physics building.

While the slides kept inside the closed drawers were still in a perfect state, a few hundreds stored in the non-closed upper drawers were seriously damaged. Their frames were covered with sticky black dust and their gelatin binder was obviously a good nutrient for mould. In photographic films and papers, the gelatin on the plastic slide is indeed an emulsion of light-sensitive chemicals (silver halide), colorants and collagen tissues. These tissues are made of proteins coming from the skin or bones of animals, usually cows. They provide food to the bacterias in the surrounding environment, and make possible their proliferation. To make a long story short, enzymes are traveling though the cell wall, chopping the protein so that the tiny subunits are absorbed into the cell that will then clone itself. The exact storage conditions throughout the years remain unknown but the environmental factors have obviously favored the growth of the fungus, thanks to a perfect combination of what archivists must avoid: high humidity, darkness, moderate temperature and air stagnation.

For how long these micro-organisms not larger than ten thousandth of a centimeter (10−4 cm) in diameter have been eating CERN patrimony - while the organization was busy looking for multiple billion-billionths of a centimeter (10−16 cm) particles ?

With the labels on the drawers and some numbers still readable on the frames, it was possible to identify that these images dated from the construction of the Large Electron-Positron Collider. They were therefore shot between 1985 and 1989 and some of them were probably slide copies of negatives properly preserved. In short, perfect candidates for the trash bin !

Despite the strong degradation of this material, Jean-Yves Le Meur, running the Digital Memory project and art passionate, decided to transfer it to the Photo Laboratory storage room, in order to check out the details of its content. The rule of CERN Digital Memory project to digitize all the analog multimedia content produced by the organization during the 20th century also applied to these decayed slides, which beauty transparently emanated through the sticky dust.

By coincidence, Matteo Volpi, particle physicist and art photographer, saw the degraded slides, and immediately proposed to evaluate their value to Le Meur - since he used to regularly run art workshops where attendees try to transform normal diapositives into pieces of art with fire, water, etc.

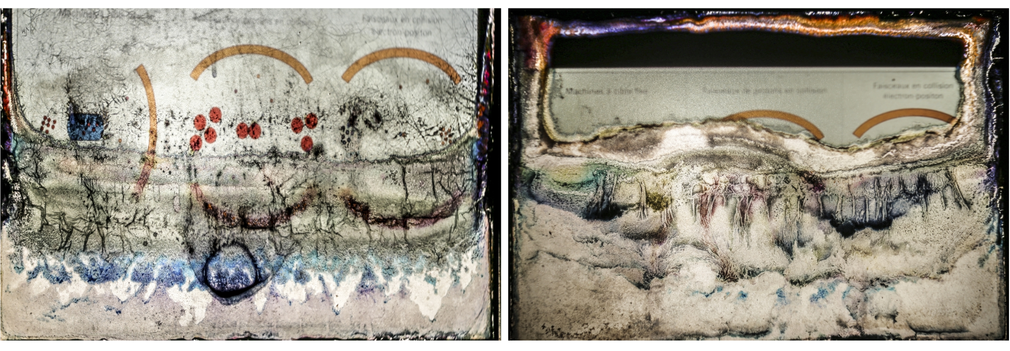

A close collaboration between the two colleagues Volpi-Le Meur (VolMeur) started with the aim to select a few hundred images among hundreds of raw slides, digitise them, and frame them as if they were paintings to expose in a museum. Different techniques to digitize the slides were considered, as it is difficult to digitise them without losing their artistic value and beautiful transparency.

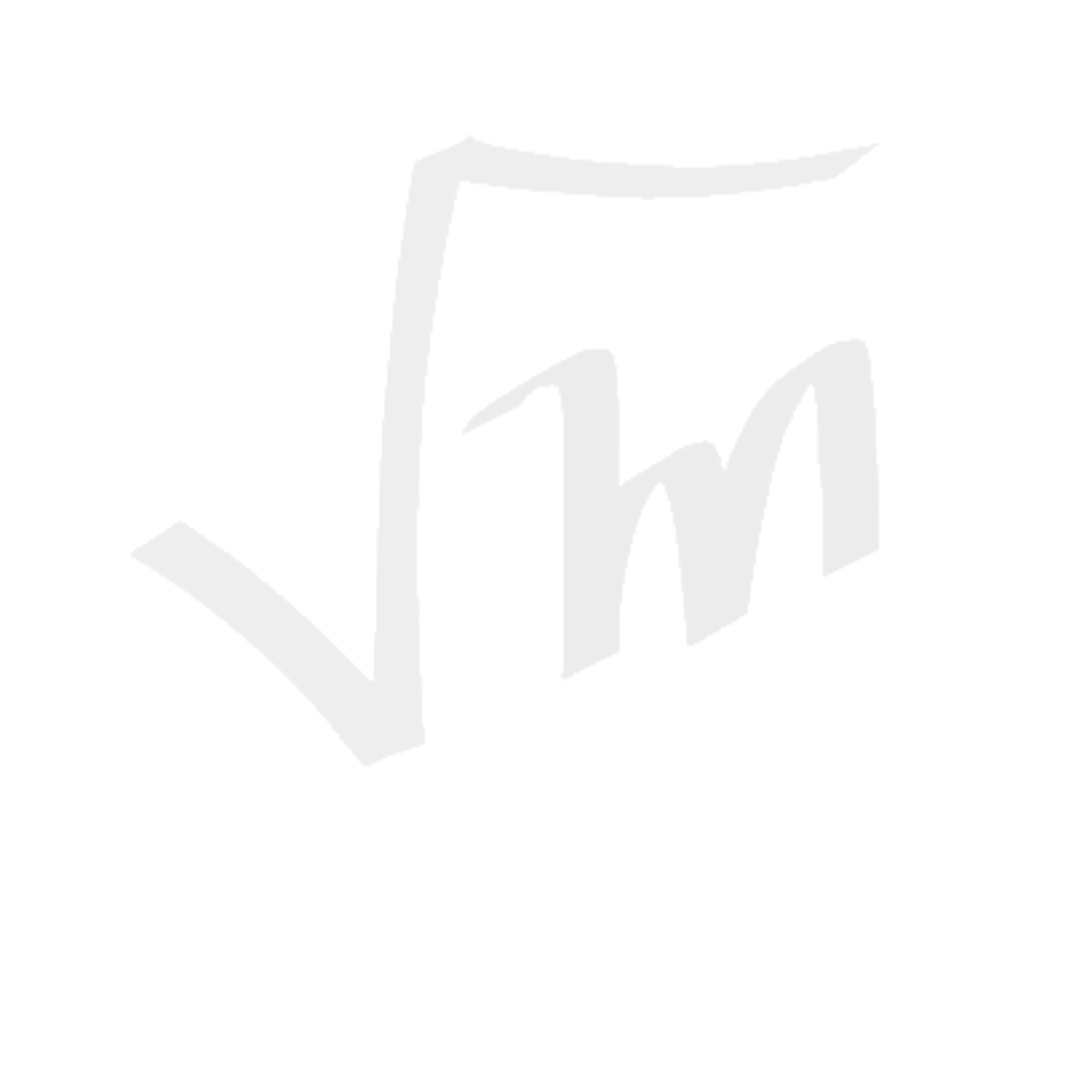

It was also discovered that some images could be well identified and mapped to the original well preserved photography. In such cases, the work of mould over time seems to be even more mysterious. It transforms the shapes and the colors but this does not seem to be governed by any predictable rules. In some cases, multiple slide copies of the same image were kept next to each other and despite being kept within the exact same (bad) conditions, the transformation by the mold ends up with very different pieces of art, 30 years later.

Learn more about the degradation process by checking out the electron microscopy of the slides, by Elisa Garcia-Tabares Valdivieso.